Millions of tourists visit San Antonio each year eager to see the Alamo and the Riverwalk. But if you like wandering around photogenic ruins that impacted history, make sure you carve some time to explore the San Antonio Missions.

My daughter and I spent a couple nights in San Antonio this summer. Staying in the Alamo Plaza, in the heart of downtown, we were within easy walking distance of all the bustling tourist activities. We toured the Alamo, strolled the shady Riverwalk, and took an evening ghost tour. We also spent a rushed morning at the San Antonio Missions, which turned out to be my favorite part of our trip.

I really wish I’d done this research about the Missions BEFORE I visited, because we missed seeing quite a few features! I’d love to go back and take my time walking around and photographing more details…

Before the San Antonio Missions existed:

The city of San Antonio didn’t even exist before the Missions. So from a historical point, it makes sense to start exploring San Antonio here.

Before 1718, there were no permanent settlements in south Texas. Instead, hundreds of small diverse indigenous groups roamed the lands for thousands of years. Collectively, these different Native American Indian bands were known as Coalhiltecans. Gradually they moved further south to escape European colonization of their ancestral lands, fighting and competing among one another for dwindling food and resources.

San Antonio Missions: Who built them and WHY?

In the 1700’s, Spain began occupying and acquiring land in Mexico and much of southern USA. The King sent Franciscan friars to Texas to expand their empire. They created walled mission communities to entice indigenous people to convert to Catholicism and become tax-paying subjects of the King of Spain in exchange for shelter, food, protection from disease and attacks from Lipan Apaches. Early missions, made from mud and thatch, were erected in eastern Texas. As the missions moved southward, to San Antonio, the structures became stone and mortar.

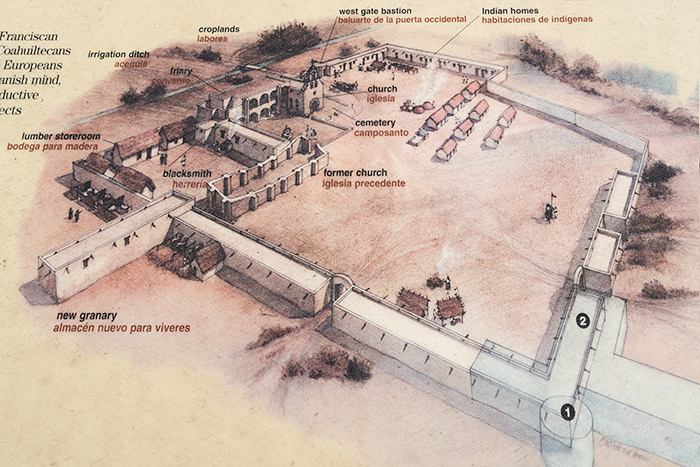

Mission Layout

The layout of a Spanish mission compound included a rectangular plaza enclosed by stone walls. Structures inside consisted of the church, Convento (for priests to live in), granary, two-room dwellings for the indigenous population inside the perimeter walls, and workshops for weaving, carpentry, masonry and blacksmithing.

Espada San Antonio Mission

Culture Change

Natives who joined a Spanish mission were forced to dismiss their own culture by adopting new names, spiritual beliefs, language (Latin and Spanish) and life skills. They no longer moved with the seasons, roaming the land as bow-hunting hunter-gatherers and warriors, but instead settled in one location, learning to use firearms and vocations to protect and support their mission community.

Lifestyle

Native converts were expected to participate in daily life dictated by the missionaries from sunrise to sunset. When church bells rang, 3 times a day, they were required to gather for prayers and religious instruction. Men worked as farmers, carpenters, soldiers, blacksmiths, stone masons or ranchers. Women spent days weaving, fishing, harvesting crops and cooking. Evenings were for bonding with group games, singing or storytelling before setting into their 2 room apartments within the enclosed walls of the mission property.

Secularization

Originally, the Colonial Spanish mission plan outlined a ten-year program. But these missions operated 60-134 years before they became completely secularized by 1824. At this time, many of the churches fell to neglect, and stone walls to ruin.

Impact of San Antonio Missions:

As people were drawn to the missions, which later became secularized, the population of San Antonio grew. Many residents in the city today can trace their heritage to one of the four San Antonio missions. Some still worship in these ancient stone churches on Sundays.

The missions provide historical insight and are protected inside the San Antonio Mission National Historical Park (except the Alamo). In 2015, all five missions received UNESCO World Heritage designation, representing “the interweaving of the cultures of the Spanish and the Coahuiltecan and other indigenous peoples.”

Preserving the San Antonio Missions allows tourists to step back 300 years and get a glimpse of early Texas history. And to understand San Antonio’s distinctive, vibrant culture which is a blend of yesteryear’s fusion, merging Colonial Spanish and American Indian art, clothing, food, pageantry and traditions.

Visiting the San Antonio Missions:

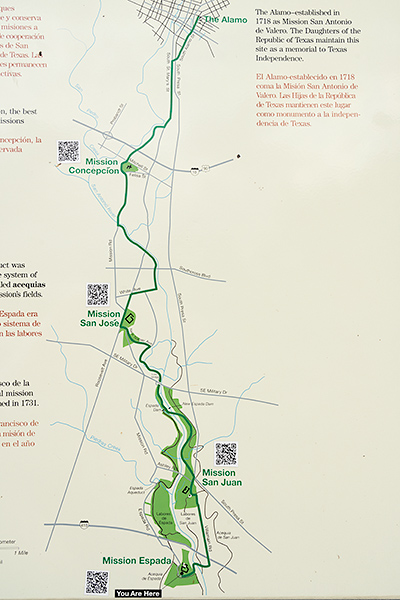

A paved road connects the four missions south of the Alamo, which are spaced 2-3 miles apart from one another. There’s plenty of free parking available at each site. Alternatively, tourists can hike or bike between the missions on the Mission Reach River Walk, a paved walkway with a total distance of 14 miles. But be careful for flash flooding, and intense heat on summer days.

Where to begin? If arriving from out of town either begin at the south end of the trail and head north toward San Antonio, or begin at the Visitor Center inside the 3rd mission, San Jose. There you can watch an excellent 23 minute film which provides a moving framework for better understanding the lifestyle of the indigenous people and the ruins you’ll see. All five missions are free to visit, have plenty of free parking and are open daily, except major holidays. Please note that many missions still hold church services on Sundays.

Driving directions to the missions: use the National Park Service to plan your route.

Exploring the San Antonio Missions Trail

Map showing layout of the San Antonio Missions. This blog post begins in the south and travels north to the Alamo:

Mission Espada (1731)

This mission was originally founded in 1690, as the very first Spanish mission in Texas. But it was abandoned 3 years later as the missionaries feared rumors that they would soon be massacred by invading French troops. This was one of 3 missions relocated here from eastern Texas in 1731.

Farming Community

Indigenous people who joined this community learned to farm, raise livestock and plant crops. They dug a dam and constructed acequias, irrigation canals, to water their crops. An onsite granary held 50 tons of corn, 35 tons of beans, chiles and salt to feed the 270 residents.

The west gate led to Rancho de las Cabras, an expansive ranch 23 miles away where longhorn cattle, sheep and goats were raised. Not much remains nowadays. This former ranch can only be visited once a month when the national park service leads guided tours the first Saturday of the month.

Espade Aqueduct & Acequia

Franciscan missionaries built a stone aqueduct supported by 2 limestone arches between 1731 and 1745. This carried water from Piedras Creek along a raised stone channel (4 ft wide and deep) to the surrounding farmlands.

Today visitors can drive a short distance from the mission and hike to the Aqueduct, now a National Historic Landmark. (We missed this completely, but recommend finding!)

Visiting

Tourists that visit Mission Espada will see a chapel with a pretty bell tower built in 1745. Surprisingly, two bells are intact in this tiered belfry. The arched stones curving around the main door are a bit of a mystery, as the end pieces don’t match the others.

During our weekday visit, we didn’t get to see inside. The church door was locked. We walked along the covered walkway past an old well that led to the two-story Convento where the current priest resides. Closed to the public, this building also houses clergy offices.

The 17 foot protective wall that once enclosed the mission compound is long gone. Likely because Mission Espada had been the most vulnerable of the five to defend, as it sat farthest from the protection of active soldiers at the Presidio (near the Alamo). Missionaries trained indigenous men to fire small canons and muskets from a fortified bastion with three-foot walls to protect the mission inhabitants.

After secularization

After secularization, the unused chapel fell into ruins. The roof collapsed, as did both side walls.

In 1858, a new priest, Father Francis Bouchu, arrived at Mission Espada and stayed until his death in 1907. He single-handedly rebuilt the fallen walls, added a tin roof and new entrance doors. Inside, he laid a wooden floor, built a choir loft, installed new pews and re-gilded the original statues on the sanctuary altar where they remain today.

Location: 10040 Espada Road

12 miles south of the Alamo/south of Interstate 410. Driving directions from the Alamo: Hwy 37 S to I-410, exit 44, follow SE Loop to Espada Rd

Mission San Juan Capistrano (1731)

This mission, established in eastern Texas in 1716 (originally named San Jose de los Nazonis) struggled to exist. The reason was twofold. First, French military troops were advancing, pushing Spanish missions out to seize the land. Secondly, there was turmoil inside the mission itself. Missionaires faced growing resistance from their indigenous converts. The Nazoni Indian tribe greatly objected to the daily religious instruction, and began blaming baptism water as the cause of disease spreading among them.

The Franciscan friars decided to move the mission to San Antonio. The Nazoni Indians did not move with them. So the mission was renamed San Juan Capistrano in honor of a courageous warrior priest from Capistrano village in Abruzzo, Italy.

In the San Antonio region, missionaries found many indigenous people eager to join. They traded protection and security within the mission walls by converting to Catholicism in order to escape hostile Apaches. By 1756, 265 indigenous people had joined the mission, and were now tax-paying citizens of Spain.

Thriving farming community

San Juan thrived as a farming community. In this dry sun baked land they irrigated fields with acequias, channeling water from the San Antonio River to their crops. Men labored in the fields growing squash, beans, corn, and melons, using ox to plough the fields. Women spent days grinding corn, making pottery, jerky, tending goats, or foraging for nuts and berries. These foods were traded for metal and other needs along the King’s Highway which stretched from Mexico City to Louisiana.

Men also worked as masons, blacksmiths or weavers as wool and cotton blankets were traded along the Camino Real too.

Church

Over time, residing converts built two churches, and began a grander one. But this final construction project was abandoned due to dwindling population.

The church that exists today has a white exterior with a tiered bell tower.

Inside the sanctuary, a long narrow hall (83 ft long x 19 ft wide) leads to the altar. The middle statue represents namesake San Juan Capistrano. Adjacent to the church is the Convento, an open, arched cloister where the priest lived.

San Juan Mission was secularized 60 years later. In July 1794, control passed from missionary to local authority. The remaining Indian families who resided at the mission (only 36) inherited land rights for tracts based on a lottery system. And the church became a place of worship for anyone in the community.

After secularization

After operating for 63 years as an active mission, San Juan became partially secularized in 1794. The residing families continued to live on the property, some nearly 100 years. And surrounding farmlands were auctioned off. But the church basically went unused, and began to collapse into ruin in 1886. In 1909, the Catholic Church oversaw restoration and rebuilt the roof, restored chapel, and opened the sanctuary for worship services again. Services still continue today.

Visiting

My daughter and I roamed around the property independently. The giant wooden doors of the white stone church opened. Stepping inside, we saw the narrow sanctuary. Lit candles flickered through openings of decorative wrought iron. Wooden pews sat under a wooden ceiling. The interior felt more intimate and rustic than the others. If I had to pick one mission interior, this was my favorite.

Archway leads to the Yanaguana trail

Behind the church, I followed a path under a stone arch which led to the Yamaguana trail. The trees were alive with noisy cicadas. A short stroll on a paved path leads to the San Antonio River where inhabitants once collected medicinal herbs and fished. Walking along the trail dwarfed by shady trees, the sound of cicadas crescendoed into a deafening symphony. We have cicadas back home in Indiana, but I’d never heard them this loud!

I didn’t see any Green Kingfishers, which are very active here in spring. The have a distinctive call from an oversized bill.

Returning to the courtyard of the Mission, I wandered along the remnants of the worn wall where families lived in two-room apartments. Windows opened into the courtyard where church bells beckoned three times daily. The back side of the their housing was solid stone wall for protection from their enemies.

The grounds were so serene. I loved the contrast of the striking green yucca plants against the stark white facade of the church with a grand bell tower. It was easy to get lost in your thoughts without any interruptions as we were practically the only ones there!

Location: 9010 Graf Road

1.5 miles north of Espada. Follow Camino Coahuilteca to Villamain Road.

Mission San José (1720)

This “Queen of the Missions” is the largest and most ornately decorated of the five. And the most fully restored.

An onsite Visitor Center has an excellent film that plays on the hour, a small gift shop and bookstore. It is also the only mission where Park Rangers lead free walking tours at 10am and 11am daily.

If you only have time for one mission visit, I’d recommend this one and the 17 minute film!

Entering the site, you’ll see the striking architecture of the Spanish Colonial Baroque church on the opposite side of the enclosed perimeter. The most famous sculpture at this mission is the unusual Rose window. Instead of being round, this window has a rectangular shape with scalloped sides. The carving represents pomegranates, not roses, to symbolize spreading seeds of Catholic faith.

Visiting

Before reaching the church there are plenty of nooks and crannies to explore along the rectangular perimeter of stone walls.

This is where the mission inhabitants once lived. Thick stone walls protected them from hostile attacks and provided respite from the intense summer heat. By 1768, 350 people lived inside these apartments inside this mission. Several rooms are open.

Step inside and imagine life for these people so long ago.

Keep following the long line of walled apartments…

On the far wall, you’ll reach a series of brick arches that lead to the church entrance.

This is where most tourists enter, but it’s not the main entrance (which we missed) on the opposite side of the church.

This is where most tourists enter, but it’s not the main entrance (which we missed) on the opposite side of the church.

Church

Father Antonio Margil founded Mission San José in 1720, two years after founding Mission San Antonio de Valero (Alamo). Construction of this striking Baroque styled church began in 1758, and finished 14 years later. A large domed cupola and bell tower topped the elegant structure.

Trained craftsmen carved ornate designs into the masonry, and painted geometric floral designs in Colonial colors on flat surfaces of the exterior. You can still see the faded design on this corner of the church. Look to the left of the tower.

Many beautiful statues adorn the orantely carved front entrance of the church, including the namesake San José (Saint Joseph) above the round window. (Don’t make the mistake like we did of not seeing this entrance! It’s easy to miss when you enter from the Convento cloisters and mistake another elaborately carved entrance as the main door. The front entrance is on the opposite side of the cloisters and not visible as you approach.)

Interior

Lifestyle

Mission inhabitants lived in the hollow protective wall that enclosed the property. Each family had two large rooms, one with a fireplace. They slept on raised beds of animal hide, with cottom sheets and wool blankets woven in the mission’s textile shop. They cooked in large ovens, hornos, outside their home in the plaza. Each resident had two sets of clothes – one for weekdays and one for weekends.

Residents planted and harvested crops, raised animals and wove textiles. And attended religious instruction and worship services daily.

A large granary with a arched ceiling painted in red and yellow decor stored food for residents of the mission. Visitors can wander through this restored structure located left of the main entrance.

Behind the church is a gristmill, built in 1764, that residents used to grind wheat into flour. Irrigation ditches powered the gristmill which churned 60 lobs of wheat into flour in one hour. Agricultural croplands existed outside the west gate of the compound, where farmers grew corn, beans, potatoes, sugar cane, melons, vegetables, fruits and cotton. This is the oldest working gristmill in Texas, as it’s still operating today, thanks to restoration in the 1930’s.

Secularization & Decline

In 1824, San José Mission was secularized. The indigenous families moved away and buildings in the compound began to decline. Roofs in both the granary and Convento collapsed. Then the north wall of the church fell down.

The most serious near-miss tragedy occurred on Christmas 1874. The large dome and roof over the main church collapsed while people were attending midnight Christmas services in the adjoining sacristy. In 1928, the bell tower fell and the spiral staircase leading up to it collapsed. All of these structures were gradually rebuilt.

Restoration

Restoration of this mission took place in the 1930’s under the guidance of Harvey Smith, a Minnesota man who became captivated by the beauty of these ruins and decided to preserve them after visiting the San Antonio missions. Other groups joined the restoration process including the Catholic Church, San Antonio Conservation Society, the City, County, State and US Government. San José is the only mission that has been fully restored. The church, still active, is run by Franciscan priests, the same religious order that founded it.

Location: 6701 San Jose Drive

2.8 mile north of San Juan. Driving: turn left out of San Juan and follow the Mission Road north 3 miles, turn left on Napier, right on San Jose Drive.

Mission Concepción (1731)

After nearly 300 years, this ancient stone church still stands. It represents the best–preserved of all the old mission churches in Texas, and is the only one in San Antonio that never suffered a collapsed roof or wall. But there’s no longer any evidence of the perimeter walls which once housed the residents of the mission, even though they were completely rebuilt in the 1760s. Secularized, then abandoned, this deteriorating church was used as a cattle barn in 1850. Five years later, the Catholic bishop gave the mission to the founders of San Antonio’s St. Mary’s University who in turn restored it, and reopened it in 1861 as a fully operating Catholic church ever since.

Today, as part of the National Park, visitors can explore the church, Convento (priest’s quarters) and remnants of the limestone quarry used to build the missions. The Convento once housed the Father President of the College of Queretaro who oversaw the San Antonio Missions Concepcion, Valero (the Alamo) and San Juan.

The striking exterior of Concepción includes twin bell towers capped by iron crosses, and a dome raised above the sanctuary. The church, dedicated to the Virgin Mary, has a round window above the door which allows sunlight to shine on the altar during the Feast of the Assumption (of the Blessed Virgin Mary) on August 15th. A Virgin Mary statue once stood above the massive doorway.

Visiting

Walking through the giant church doors, we passed an ancient stone stairway under a Moorish arch. Gated, we couldn’t enter. But the stairs led to the Infirmary–where a window overlooked the sanctuary, so the ill could still attend mass.

Tucked into a small room near the sanctuary, under another arch, was the Baptismal. Church records show that between 1731 to 1762, 792 indigenous people were baptized here. Distinct carvings decorate the Baptismal under a fresco of a crucified Christ.

Tucked into a small room near the sanctuary, under another arch, was the Baptismal. Church records show that between 1731 to 1762, 792 indigenous people were baptized here. Distinct carvings decorate the Baptismal under a fresco of a crucified Christ.

Inside the chapel, a magnificent dome, encircled in windows, shed natural light on the altar below. The acoustics in this vaulted space must’ve been amazing.

Wandering around the nooks inside the thick stone walls of this Spanish mission felt reverent.

Our voices instinctively dropped to whispers as we admired the ancient architecture and studied fading frescoes painted on walls, arches and ceilings.

Frescoes painted in blue, red, yellow and black colors, created from natural plants, had faded to stencils in places. Geometric artwork once embellished the interior and exterior of Concepcion, honoring both indigenous beliefs and Spanish Catholic symbolism.

A fresco with radiating rays called The ‘Eye of God’ painted on the ceiling of the library in the priest’s quarters is the most famous artwork at this mission. However, years later, when layers of soot were uncovered by a conservancy Los Compadres, another eye, mustache and goatee were revealed—changing the interpretation of this fresco to a Spanish medallion or Viceroy, instead of the eye of God. Striking as it was, we somehow completely missed seeing it.

But we did see this fresco on the ceiling. And faded ones on the walls.

Even though this was a small site, this was still my favorite mission church to get (imaginatively) lost in. Those frescoes and thick adobe walls–rough and untouched–drew me in. What mysteries and stories these walls could reveal.

Location: 807 Mission Road

3 miles north of San Jose. Driving: retrace route back to Mission Road and turn north (right).

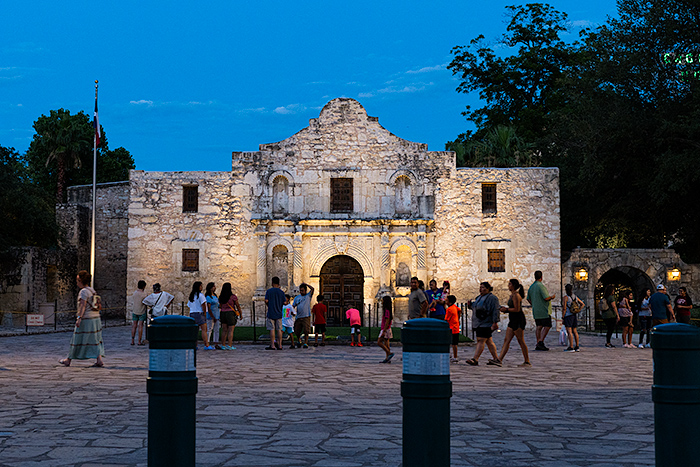

Mission San Antonio de Valero, aka the Alamo (1718)

“Remember the Alamo!”

U.S. soldiers used this battle cry to ignite their desire for independence from Mexico during the Mexican-American War of 1846-48. The Alamo symbolized the heroic resistence of 200 Texans who unsuccessfully attempted to ward off thousands of Mexican soldiers who swiftly defeated them in the 1836 Battle of the Alamo.

Most people remember the Alamo symbolizes Texan’s fight for Independence. Millions of tourists visit this historic site each year.

But what people might not know, though, is that the Alamo began, not as a fortress, but as one of the five San Antonio Missions. This was, in fact, the first San Antonio mission erected along this historic trail.

Francisan friars established the Mission San Antonio de Valero (commonly known as the Alamo) along the river in 1718. Under Spanish orders, a military garrison was also set up nearby. The mission built twenty buildings including long barracks for housing.

By 1744, over 300 Indian converts resided here. They supported the mission by raising cattle and sheep, growing corn, beans and cotton to produce textiles, clothing and food. But by 1777, the population dwindled to only 44 people.

Entrance to the Alamo…

Church

Construction of this stone church began in 1756, after flash flooding and a 1724 hurricane necessitated moving locations twice. But faulty construction caused walls, arches and portions of the roof to collapse a few years later.

The third story was never built, neither was the dome or grand bell tower. It was never fully completed in all the years it served as a mission. Nor did the inhabitants ever worship here (as the construction was never-ending).

The curved parapet on front of the church you see today was constructed by the US Army who repaired the ruins in the 1850’s.

Inside, there is not much to see that resembles a church. Empty rooms line the stone walls.

Plaques identify heroes who fought bravely at the Alamo. A few exhibits record the history. Photographs are permitted inside as long as you don’t use flash.

Plaques identify heroes who fought bravely at the Alamo. A few exhibits record the history. Photographs are permitted inside as long as you don’t use flash.

After secularization

Valero was secularized in 1793, and tracts of land were divided among the few Indian families who resided there. Ten years later, due to increasing threats from French Louisiana, Valero became a defensive fortress in 1803 and was occupied by a Spanish Army. (These soldiers came from a village, El Alamo, in northern Mexico. Thus the name change.) Then the mission became a political prison. Then San Antonio’s first hospital. Then back to being a fortress…and the rest is history.

Ancient well at the Alamo

Visiting

Visitors can tour the Alamo chapel for free (but must reserve a time online), rent audio tour phones or take a guided tour. It remains a busy place year round. Quietest time to visit is first thing in the morning.

There’s no charge to wander around the fenced property, open 9-5pm. The site contains 3 surviving buildings. Inside the long barracks, you can watch a short film. In the garden, there’s a fountain, old well, and statues of historical people important to the Alamo.

Visitors can also purchase tickets to the Ralston Family Collections Center to see Phil Collins’ and Donald and Louise Yena’s private collections of Spanish Colonial artifacts.

Exiting the Alamo will bring you to the Alamo Plaza. Straight ahead, a few steps away, is the historic Menger Hotel and beyond it is a large shopping mall. Turn right, walk across the street and go a couple blocks to reach the pedestrian River Walk.

Exiting the Alamo will bring you to the Alamo Plaza. Straight ahead, a few steps away, is the historic Menger Hotel and beyond it is a large shopping mall. Turn right, walk across the street and go a couple blocks to reach the pedestrian River Walk.

Location: downtown San Antonio, 300 Alamo Plaza

4.4 miles from Concepcion Mission

Parking

The Alamo is located in a bustling tourist area downtown San Antonio where parking can be expensive. Compare rates and check distances for potential parking spots in advance by looking online at either the City of San Antonio Public Parking site or Parkopedia (site I preferred as it listed more lots/garages, costs and walking distances to different attractions).

The garage cloest to the Alamo with the most reasonable rates that we found: Riverside Mall Garage #1 (300 E Crockett Street)— $5 for one hour, $25 for 24 hrs. Rates are even less in open public parking lots scattered around town. And if you can snag one, parking spaces on the street are free Sundays.

Tip: to save money on parking consider visiting the four Spanish San Antonio missions south of the city first—where parking is free and plentiful— before heading downtown. (Or last on your way out of town.) Once parked downtown you can walk most everywhere. The Alamo, the River Walk and the Riverside Mall (IMAX shows about the Alamo) are just a 3-5 minute walk away from each other.

~~~~~~~~~~~~

Pin a pic to save for later!

JaNeal Smith - Extremely full of detailed research, Kim. After having been to this mission a few years ago, I appreciated all the history and photos. Thank you so much for this well written blog. I will look at this area with fresh eyes. Thank you.

Kim Walker - Thank you, kindly!! Knowing a little of the history makes such a difference when you visit. Wish I had done more research before I went…