Visit Dunfermline…and walk in the shadows of royalty.

Once upon a time, in the Kingdom of Fife, people visited Dunfermline to see the king. Or, more frequently, the queen.

THIS is where Kings & Queens ruled and raised heirs for future thrones. And where monarchs built their palace inside Scotland’s grandest monastery. Dunfermline became so important that Bishops visited. Abbots. Royals. Nobles. Even the Pope sainted one of the queens. It was THE final resting place for Scottish royalty–and others who could afford burial in the striking Abbey.

And— it was a place of miracles! People from faraway lands traveled here to be healed or blessed by the Queen. And kept coming even after her death—for hundreds of years!

~~~

So imagine my surprise when my daughter and I arrived to visit Dunfermline, and found a busy, modern city without any reference to its past. At least at first glance.

First Impressions

Unlike the charming medieval villages we’d visited elsewhere in Fife, this city (population 50,400) is the largest. It has a huge Amazon fulfillment center, train station and shopping mall. Heading down a maze of narrow streets, we saw buildings of ancient stone, art deco and contemporary glass. We passed locals hanging around open-doored pubs, an occasional shopper, and young mums pushing baby carriages past vacant beauty salons. Lots of cars, buses and taxis— but no signs pointing the way to sites in the historic center.

When we entered our hotel near the old market square, there was no desk attendant, bell, or indication that we were supposed to enter the tavern next door and find a manager to check us in. Nor any tourist brochures about historical sites, maps to the landmarks, or ads for guided tours.

It was almost as if this ancient city wanted to keep its secrets hidden.

Had we not known that Dunfermline was Scotland’s ancient capital, and planned what to see in advance, we could’ve completely missed out on these special gems.

TOP HISTORIC SITES TO SEE?

First, you must travel to the Historic District, on the very western edge of the city. Once there, you’ll find Dunfermline Abbey, Dunfermline Palace and Pittencrief Park located within walking distance of one another. Plus these other sites: Dunfermline History Museum, the Carnegie Library and the Carnegie Birthplace and Museum. All highly recommended!

Hours vary per season. Tickets for Abbey (Nave & church closed Sun & Mon) and Palace (check if open yet) must be pre-booked online through Historic Scotland and Abbey Church during the Covid pandemic.

Visit Dunfermline Abbey Nave

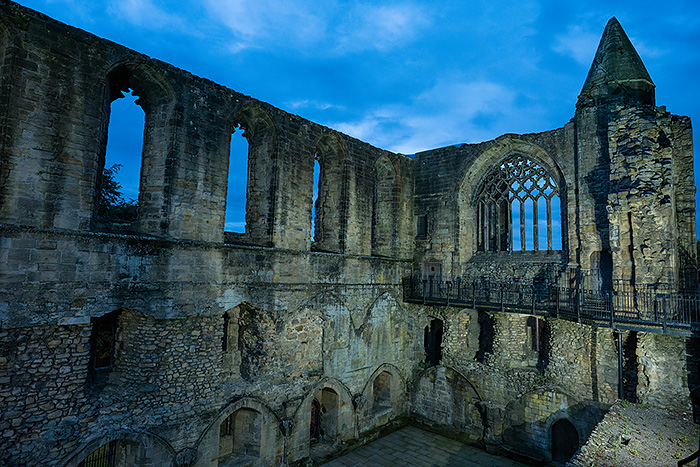

Dunfermline Abbey is the city’s definite highlight! This striking Romanesque masterpiece actually has two separate parts. The original Abbey, called the Nave, sits in the back of this magnificent building. Built in 1070, it began as a priory for monks when Queen Margaret founded Scotland’s first Benedictine monastery. The Abbey Church, rebuilt in 1821, still holds Sunday worship services in the front, east end.

Somewhat hidden entrance–no signage!

Dunfermline Abbey sits in the middle of a large churchyard cemetery. It can be a little confusing to find the right entrance. The massive door facing the park is no longer operational. The door on the opposite end enters the more modern church. The stone ruins adjacent to the south side belong to the sprawling Palace and Monastery that connected to the Abbey at one time.

Nave

We walked around the cemetery, admiring this massive structure, all the while looking for the door to the historic Nave. Reaching the south side of the building, we saw an opening inside this beautiful arched doorway. Free to enter, there was no ticket collector or docent. We walked inside…

Stepping into the impressive Nave with its carved pillars, lofty arches and stained glass was downright humbling! Natural light streaming through the windows and reflecting off the warm wooden ceiling created a golden glow.

The sheer grandeur inside this space quelled our conversation to hushed tones. Because it just feels reverent.

But, the more we wandered—we felt a palpable disconnect. There were no explanations to interpret what we were seeing. Or descriptive pamphlets. This was an important burial ground for kings, queens, princes and a revered saint— yet, where? Memorial markers on the walls had faded text no longer legible.

Who was buried here? What were their stories?

We heard some information later, when watching a short film about the royals in the History Museum. But to be honest, I learned most of Dumfermline’s history by delving into online sources once I returned home. And only then could understand the sites more fully.

(I spent waaay too many hours researching and learning the history of the people associated with Dunfermline for my own personal interest, and decided to share it on this blog post as the comprehensive info simply doesn’t exist in context anywhere that I could find.)

Interpreting history before you visit Dunfermline

Interpreting history is like putting together a jigsaw puzzle. When you connect details—how people were related, or identify motives behind actions–the assembled pieces suddenly make sense as a whole. Only then can centuries of history unfold, giving meaning to the ruins, and unravel secrets from the past.

Abbot’s House where the Benedictine Abbot of the Monastery lived.

So…Who were the Kings and Queens in Dunfermline?

King Malcolm III

This king was already living in Dunfermline, but put it on the map when he married English-Hungarian princess Margaret here—waaay back in the 11th century. It quickly became a royal city. Then Scotland’s capital—where subsequent kings wanted to reign and be buried. So, who was he?

Let’s begin with his dad. King Duncan. Yes, the same King Duncan in MacBeth!

King Duncan only reigned 6 years before his death. In Shakespeare’s play, he was depicted as an old king who Macbeth murdered in his sleep. In real life, however, he was 40 years old when Macbeth killed him in battle. Duncan’s son Malcolm was only 9 yrs old at the time, and his brother Donalbane 4. So they were sent away for safety–Malcolm to England to serve in Edward the Confessor’s court and Donalbane to Ireland with their mother– exiled while Macbeth ruled for the next 17 years.

In 1057, Malcolm came for his revenge. At age 26, Malcolm slayed Macbeth. (Yes, the same real people and events in Shakespeare’s famous play–who knew?)

There was still a snag. Macbeth’s stepson had advanced to the throne. Months later, Malcolm killed him, and was crowned King Malcolm III.

Crowned King of Scotland

Malcolm (Canmore) III went on the reign as King of Scotland for 35 years. He ruled during a turbulent era, but strove to keep peace with the English. All was well for the first nine years until King Edward the Confessor died. Then the Norman invasion began, and William the Conqueror swept in to take the English throne.

Malcolm was a brave, strong king who demonstrated great leadership. Not afraid to confront his knights when they were tempted to act against him, Malcolm earned their loyalty. He led 5 raids into England, at times ignoring peace treaties, in repeated attempts to expand his territories.

Malcolm Canmore married twice. His first wife, Ingibjörg, was the powerful Earl of Orkney’s widow. This union helped secure peace with Norse rulers of Scotland’s northern territories. They had 3 children during their 4 year marriage before she died.

His second wife was Margaret. According to some historians, he was smitten when he met her 9 years prior when they were both serving in Edward the Confessor’s English court during his 14 year exile.

Apostles on ceiling of the Nave

Saintly Queen Margaret

When Margaret was 10 years old, the aging and childless King Edward had invited her family to return to England (from Hungary) as her father Eadward was the legitimate heir to the throne. However, soon after they arrived Margaret’s father died. Nine years later, despite her brother Eadward (Jr.) being the rightful heir when King Edward died in 1066, bloody uprisings between the clashing Normans and Saxons caused the family to flee.

But a storm blew their ship off course. The ship struck the coast in Fife, near Dunfermline. King Malcolm III offered protection to the entire family. Then a swift marriage proposal. But Margaret refused. She was devoted to becoming a nun.

Malcolm was persuasive. But so was she!

They wed 3 years later, in 1069, in Dunfermline. A Culdee (Celtic) bishop from St. Andrews married them in a small church dating from 800 AD. This was Scotland’s first Christian church. (They would later build over it to create Dunfermline Abbey). Their lived in a stone tower castle in the nearby wood, now Pittencrief Park.

Being very religious, Margaret convinced Malcolm to bring in Benedictine monks from Canterbury, and establish a priory. This grew and became Scotland’s first monastery.

Cellars in monastery

Margaret persuaded Malcolm to build a bigger church, Holy Trinity, where the small chapel had been, for the growing number of visiting nobility. She instigated reforms to change the Celtic church into a Roman Catholic church. And convinced Malcolm to use Anglo Saxon language, not Gaelic, in both church and court.

No doubt they were a contrasting pair. A warrior king wed to a saintly queen–yet they had a strong marriage with love and respect and produced 8 children. Three sons became kings. And all are buried in the Abbey.

Humble and pious, Margaret faithfully served the poor. She fed orphans from her own spoon, and washed the feet of pilgrims. She spent long hours praying in a cave, reading her Bible and fasting. Margaret had divine healing powers and performed many miracles.

As news of the miracles spread, people began making long pilgrimmages here despite difficult travel conditions during the Middle Ages. She built a ferry for pilgrims to cross the Firth of Forth between Edinburgh and Fife– still known as Queensferry today.

Hostilities with England broke out again when the son of William the Conqueror, William Rufus, reigned in 1093. During the Battle of Alnwick, King Malcolm III was ambushed by the Earl of Northumbria, and died at age 62. Edward, his oldest son with Margaret, also died in that battle.

The 47 year-old Queen, who had been staying at Edinburgh Castle, was so striken with grief that she too died, just 3 days after hearing the devastating news. Malcolm’s younger brother Donaldbane seized the Scottish throne, joined forces with the King of Norway and began attacking Edinburgh Castle. Margaret’s body, still inside, was secretly moved from Edinburgh Castle to Dunfermline Abbey. Her sons and attendents carried her through a hidden castle door and escaped from enemy sight in a thick mist that camouflauged their journey.

She was buried in Dunfermline. People continued traveling here long after her death. They spent the night at her grave, praying, in hopes of waking up cured.

Margaret’s Miracles

Miracles drew people to Dunfermline for hundreds of years. Monks used strict rules to measure accuracy of miracles and kept detailed records in their written collections.

In the Miracula of St Margaret, 45 miracles occuring to 9 monks, 3 priests, an abbot and 32 lay people were authenticated. One account describes an English woman who had visited sainted shrines around England and France for 7 years without any divine intervention. But, the story goes, when she traveled to Dumfermline, and prayed at St. Margaret’s shrine, she was immediately healed.

Miracles recorded in the Miracula included curing paralysis, strokes, insanity, demon possession, muteness, tumor, dropsy, elephantiasis, abscessed teeth, leprosy, freeing swallowed lizards, and blindness.

Even kings came to pray at her grave. William the Lion spent a night seeking answers about whether or not to initiate another invasion of England. And William Wallace came to spend the night with his mother, no doubt praying for divine intervention and protection from his enemies.

In 1245, visiting pilgrims reported seeing bright flashes of light coming from her grave. Bishops of St. Andrews, Dunkeld and Dunblane investigated the claims as proof of her sanctity. Once authenticized, Pope Innocent IV cannonized her as a saint in 1249.

Queen Margaret’s chapel and shrine (blocks in foreground) where pilgrims came for healing.

Sainthood

The belief that relics of the saints could perform miraculous healings was widespred during this time. Above her decorated casket was a stone casket containing some of her relics (bones or belongings) that were believed to have supernatural powers and used for special purposes. This “feretrum” practice included loaning out Margaret’s nightdress to pregnant queens to aid their deliveries (present at the births of James III and James V). But the strangest request came from Mary Stuart Queen of Scots who paid a handsome fee to rent Queen Margaret’s head during the birth of her son.

A year after becoming a saint, Margaret’s remains were transferred to a new bejeweled shrine on the east end of the Abbey. Her descendent King Alexander III, 7 bishops, 7 earls and royals witnessed two miracles during this process. The first miracle was the Odour of Sanctity, which is a supernatural pleasant smell coming from a spiritual person after death. When dirt was shoveled away and her body was exhumed from the grave, a strong overpowering smell of perfumed flowers filled the air.

The 2nd miracle happened when pallbearers were carrying her remains. When they passed Malcolm’s grave, Margaret’s tomb suddenly became so heavy that the puzzled men could not advance. A Bishop called out that perhaps Malcolm’s tomb should be opened and his bones joined with Margaret. When King Alexander agreed to have this done, the pallbearers could lift her tomb easily and moved the royal pair’s reunited remains to the shrine.

Today only the dark gray stone base of her shrine remains. The rest was completely destroyed during the Reformation in 1560. Tourists can visit her cave, although the original entrance has since been covered by a parking lot.

Admiring the Nave where Royals are buried

King David

David was the 8th and youngest child of Malcolm III and Margaret. During his childhood he lived in England, in the court of brother-in-law King Henry I.

Older brother King Alexander I, who ruled from Stirling Castle, began work to enlarge his mother’s Holy Trinity church into Dunfermline Abbey in 1126. He built the two towers looming over the carved doorway at the western entrance, the stunning window above it, and the high gable roof overhead.

David succeeded the Scottish throne after brothers Edgar I and Alexander I died, and reigned until 1153.

King David was a pious man, like his mother, and founded many abbeys including Melrose, Dryburgh, Holyrood and Dunfermline. The intricately carved interior of the Abbey you see today is because of him.

In 1128, David’s request for an Abbot from Canterbury was granted. The status of his mother’s church, Holy Trinity, was elevated to an Abbey in 1150. He hired the finest stone masons to expand the structure into a grandoise Romanesque Abbey, and carve elaborate designs into the echoing nave to become an important mausoleum, where his royal parents were buried. And added the Monk’s Choir and the St. Margaret shrine to the east end.

Geoffrey of Canterbury served as Abbot of Dunfermline until his death in 1154, and was buried in the Abbey. He witnessed the Abbey become Scotland’s wealthiest monastery over his tenure.

King David also established Dunfermline as a royal burgh, introduced feudal tenure into Scotland, and rebuilt many area castles including Edinburgh and Stirling. He also honored his mother’s memory by building St. Margaret’s Chapel at Edinburgh Castle on the very spot where she died in 1093.

He acquired many lands, and drew important aristocratic families from France to settle in Scotland during his rule. Bruce, Stewart, Comyn, and Oliphant are among the noted names who intermarried with Scottish aristocracy. David lived a long life and was buried in Dunermline when he died at age 73. He outlived his sons, so the successor to the throne was 12 year-old grandson Malcolm IV. But he cowered under pressure and surrendered Cumbria and Northumbria to Henry II, the King of England. (And thus the English rule began…)

Steps lead to the Abbey Church. The only sign in the Nave points out the apostle portraits on the ceiling.

Fast forward past English Kings ruling over Scotland…

Sir William Wallace

In 1297, William Wallace led the growing resistence in Scotland against English rule in a war of independence. He won the battle at Stirling Bridge and proclaimed himself Guardian of Scotland.

King Edward I of England, who was ruling Scotland remotely, invaded the country and defeated Wallace. William promptly went into hiding. One of the places Wallace hid– quite often– was Dunfermline. He sought refuge inside a well and a four-foot cave in the heavily wooded Glen of Pittencrieff Park, adjacent to the Abbey.

King Edward’s troops descended on Dunfermline and destroyed the domestic buildings on the south side of Dunfermline Abbey in 1303. But they left the Abbey Church alone. Perhaps they were scared of the saint’s supernatural powers from the grave. Or perhaps because of mere respect for her connection and support of the English Benedictine Order in Canterbury.

Later in 1303, Wallace returned to visit Dunfermline again. This time, accompanied by his mother, they traveled on foot for 43 miles from Dundee to pray at Saint Margaret’s shrine. His mother unexpectantly died during the night. He quickly buried her in the Abbey church cemetery and planted a Hawthorn sapling to mark her spot. A memorial was later added under the Hawthorn tree which exists in the northern end of the cemetery. (Was unaware of this when we came to visit Dunfermline.)

In 1305, William Wallace was captured near Glasgow. He was taken to London, brought before King Edward, and tried for high treason. Stripped naked, Wallace was dragged by his heels from a horse through the streets to the Tower of London. A gruesome, torturous death followed. He was strangled by hanging, but removed while still alive, emasculated, quartered and beheaded. His head was dipped in tar, and placed on a spike above the London Bridge as a warning to others.

John Blair, a Benedictine monk in Dunfermline had been appointed as Wallace’s chaplain. Ironically, they had attended the same school in Dundee. Blair collected William’s confessions, accompanied him on many battles, and wrote Wallace’s biography after his savage death. Intent on giving Wallace a proper Christian burial, Blair gathered supporters and traveled to Newcastle, Berwick, Stirling and Perth to collect Wallace’s dismantled body parts. Back in Dunfermline, the monks buried Wallace’s remains beside his mother under the thorn tree.

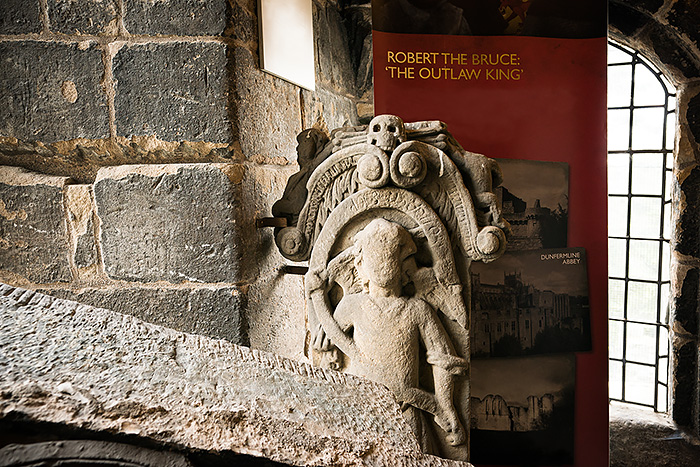

Robert the Bruce

Robert Bruce replaced William Wallace as Scotland’s Guardian. King Edward I regarded him as a traitor and made every effort to crush his act of rebellion, as Bruce attempted to free his people from English rule.

Scotland was defeated by English troops 3 months later, and King Edward I was recognized as Scotland’s ruler.

In February of 1306, Robert lured his strongest rival, John Comyn, to Dumfries in southern Scotland. Both were leading Scottish nobles, but had fought on opposing sides of the war between the English and Scots. Their agreeable meeting to discuss matters quickly turned ugly. Tempers flared. Angry outbursts turned violent. Accusing Comyn of treachery for siding with King Edward, Bruce swiftly stabbed him.

The place, more than the act, was shocking. Robert had murdered Comyn inside Greyfriars Church. The Pope promptly excommunicated Robert for this sacrilegious act. But the Bishop of Glasgow bestowed absolution for his sins a few weeks later, providing him clearance to bid for the throne.

Robert the Bruce claimed the Scottish throne as the rightful heir–being the great-great grandson of David I. He immediately began the uprising against Edward I, and six weeks later was crowned King of the Scots on March 25, 1306.

But the English didn’t take defeat so easily. By October, Bruce and his allies had been defeated three times by English and Scottish enemies.

Bruce fled from the mainland and went into hiding from King Edward I, who was hot on his trail. (Knowing how his predecessor died, who can blame him?)

To retaliate, King Edward turned his attention instead on punishing Bruce’s family…

Bruce’s family

English troops hunted down Robert’s family who had spread out for safety. The troops quartered and executed his 3 brothers. Then imprisoned his second wife Elizabeth, his 10 year-old daughter Marjorie (from 1st wife Isabella who died in childbirth, age 19), and his two sisters.

All four women were held in solitary confinement at different convents in England for 8 years. Bruce’s sisters were displayed daily in wooden cages, like zoo animals, for public humiliation. The King built a cage for young Marjorie, but then decided it might be a bit much. Elizabeth was given the lightest sentence, as her Irish father was King Edward’s closest friend.

Seven years after King Edward’s death, the women were finally released. Marjorie and Elizabeth promptly returned to Scotland in 1314.

Marjorie married Walter Stewart, the man who brought her back to Scotland. But she died 2 years later, at age 20. Pregnant at the time, she had a horse riding accident and died during childbirth. Her son, born premature, later became King Robert II of Scotland, beginning the Stewart line.

Years later in 1327, Bruce’s wife, Queen Elizabeth, died at age 43, while visiting royals in Cullen. She, too, fell off her horse.

Independence at last

Bruce came out of hiding after a year (after being inspired by a spider). He fiercely led his people toward independence, fighting against the English who repeateldy attacked. Robert the Bruce perserved as the fighting ensued— for 22 years!

King Robert led a string of military victories between 1310 and 1314, gaining control of much of Scotland. At the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, he crushed King Edward II’s army, and established independence for Scotland. But Edward II refused to admit defeat or renounce his control over Scotland. Nobles submitted a declaration to the Pope declaring King Robert as the rightful monarch of the independent kingdom. And in 1324, Pope John XXII finally agreed. Scotland was free!

Robert the Bruce lived at Dunfermline Palace only a short while. His only son, David, with second wife Elizabeth de Burgh was born in Dunfermline Palace on March 5th, 1324. He financed the restoration of Dunfermline Abbey and Monastery when it was damaged during the Wars of Independence.

Robert the Bruce sculpture at Dunfermline Palace

A year later, Robert the Bruce decided to move south. He acquired lands west of River Leven in Loch Lomond, and built a country mansion with a moat, falcon aviary and hunting park.

He became afflicted with an illness a couple years later, in 1327, sadly the same year his wife died from her horse riding accident. When his physical condition worsened gravely the following year, and he realized he was dying, he made his last voyage. He sailed to Whithorn, the southern tip of Scotland, to visit St. Ninian’s cave and shrine. There, at Scotland’s birthplace of Christianity, he fasted for 4 days praying for miraculous healing and his soul.

(We visited this delightful area– Dumfries, Whithorn and Wigtown–on a road trip heading south of Edinburgh. Check out this blog post for itinerary ideas!)

Once home, King Robert donated large sums of silver to religious organizations along with requests for prayers. He repented of his vow to embark on a crusade to the Holy Land, and made arrangements for his heart to be removed at death and taken on a pilgrimmage before being interred in Melrose Abbey.

Robert the Bruce and Edward III signed the Treaty of Edinburgh in 1328, which secured Scotland’s lasting independence from England. And the Wars of Independence officially ended.

A year later on Jun 7, 1329, Robert the Bruce, age 54, died at home. The cause of his death is unknown. Initially recorded as leprosy, later physicians who studied his medical records and bones claim that diagnosis is incorrect. Instead, he likely died from tuberculosis, ALS motor neuron disease, cancer or stroke. He could barely move or speak by his final days.

Bruce left detailed instructions about his funeral in advance and commissioned a white marble casket from Paris. A Templar Knight carried Bruce’s heart through the Holy Lands to Jerusalem but was murdered in Spain. Crusaders brought Bruce’s heart back to Scotland to rest at Melrose Abbey. And a ceremonial burial of his body followed at Dunfermline Abbey.

He was buried beside his wife, Queen Elizabeth, in an alabaster tomb decorated with gold leaf in the very centre of the Abbey beneath the high altar. Their daughter, Matilda, was also buried in Dunfermline Abbey.

During the Reformation, when Calvinists were attacking Abbeys, the tombs of the royal couple were ‘lost.’ Perhaps hidden for safe-keeping? Or hidden under all the debris when the tower fell? King Robert’s tomb was rediscovered in 1818 during construction work on the new Abbey, and Elizabeth’s tomb was rediscovered 100 years later. Both were re-interred in the Dunfermline church Abbey.

Robert the Bruce’s tomb inside the Abbey Church

Scotland’s national hero and warrior king was buried in Dunfermline Abbey along with other kings. But only his memorial is easily identified. He lies beneath the High Alter marked by a golden engraving inside the Abbey Church.

The inscription “King Robert the Bruce” is carved in stone on the Dunfermline Abbey tower above his burial place. Everyone who comes to visit Dunfermline can see at first glance the importance of this Scottish king held in highest esteem.

David II

The only surviving son of Robert the Bruce was born in Dunfermline in 1324. His mother Queen Elizabeth died when he was only 3, and she was buried in the Abbey. Young David was crowned king at age 5 when his father died. Quickly married to secure peaceful ties with England and France, he wed incredibly young. He and his 8 year old wife, daughter of King Edward II and Queen Isabella from France, were exiled to France until he was old enough to govern his country.

At the age of 17, he returned to Scotland but not to Dunfermline. David invaded England a few years later, was wounded, captured and imprisoned for 11 years. He struck a deal to be set free: Scottish nobility would pay his ransom–10,000 marks per year. Despite having had 2 wives and several mistresses, he died childless. Nephew, Robert II, succeeded him to the throne.

South side entrance to the Nave

King James I

Born in Dunfermline Palace in 1394, James was the youngest son of King Robert III and his consort, Queen Annabella Drummond. His mother died when he was 7. A year later, when his oldest brother suspiciously died while visiting ruthless uncle Robert Steward, Duke of Albany, young James was whisked off for safe-keeping in France. But English pirates captured his ship, and transported him to King Henry IV in England. Instead of being a prisoner however, he was educated and groomed to develop respect for the King and their ways. He joined English forces to march into France and at times fought against the Scots. He married Englishwoman Joan Beaufort in 1424, just prior to his release.

Robert Stewart, Duke of Albany was the last royal family member to be buried at Dunfermline Abbey. He died in 1420 while acting as regent during James’ time in England.

Returning to Scotland at age 29, James took revenge on his uncle the Duke of Albany (for murdering his brother) by attacking his son Murdock, and grandsons. This also removed any threat to his power, as the Albany Stewarts were acting as regents in Scotland during the king’s absence. James ruled with an iron fist for 13 years. Over time, he diverted the annual ransom payments for his release from England to construct the lavish Linlithgow Palace.

Although family, the Stewarts were sworn enemies of King James, and plotted his death.

His uncle Walter led a surprise attack when King James and his queen were spending Christmas at Blackfriars Monastery in Perth, his favorite city. James loved to play tennis there often extended his holiday. On the night of Feb 20, 1437, James was relaxing with the queen when they heard a flurry of horses approach. James hid under the floorboards as there was no other escape route, as the drainage pipe was blocked with tennis balls. The queen and her ladies attempted to hold the door, but the assassins broke through. Perplexed initially, they eventually heard him under the floorboards, jumped in and stabbed him to death. Queen Joan escaped and made her way to Edinburgh Castle to alert their son, who became King James II.

The murder of King James officially marked the end of Dunfermline being the nation’s capital. Administrative power transferred to Edinburgh where royals could be better protected.

Decline of Dunfermline

Important buildings connected to the Abbey were attacked during the Wars of Independence and the Reformation. English King Edward’s troops overtook the Abbey and wintered here in 1303. When they left, they burned the monk’s residential buildings and destroyed other buildings, but largely left the Abbey intact. Then in 1560, mobs sacked Margaret’s shrine, Palace and Abbey during the Reformation, when the country separated from the Catholic church.

Monks and royals abandoned the city, and historical buildings fell into disrepair. Locals reclaimed the Abbey Church, as their Presbyterian parish, in the next decade. David Fergusson, Chaplain to King James VI, became the first Presbyterian Minister of Dunfermline Abbey.

King’s master stone mason’s tomb inside Nave

King James VI

Mary Queen of Scots delivered James, her only child, in Edinburgh Castle in 1566. To ease the difficult birth, Mary had sent for St. Margaret’s relic, specically her head, to ensure a safe delivery. James was a frail baby, grew up short with bent legs which affected his walking for life. His father, Lord Darnley, was murdered in February the following year. Four months later, when James was 13 months old, his mother was imprisioned for her Catholic views and forced to abdicate the throne. Following a sermon preached by Protestant Reformer John Knox, baby James was crowned king in Stirling.

Raised by four different earls in Stirling, young James was groomed to hate his mother, embrace Protestant beliefs and appreciate the arts. Although Mary Queen of Scots attempted to reunite with her son over the next 20 years, he ignored her and never saw her again. When Mary later escaped, and eventually sought refuge with her cousin, Queen Elizabeth, Mary was imprisoned and executed in 1587. James, aware that Elizabeth was aging and childless, saw his opportunity to succeed to the English throne, and began communicating with her and her council by code.

Moving to Dunfermline

In 1587, King James VI fled the plague in Edinburgh and arrived in Dunfermline to establish his residence. He renovated ruined buildings, and built a new palace as a wedding present for his 14 year old bride, Queen Anne who was arriving from Denmark in 1589. At sea, a violent storm caused the Danish Admiral to turn the fleet around and seek shelter in Norway. Two months later, 23 year-old James left Scotland to retrieve his wife himself. They married in Oslo late November, and traveled around Europe before sailing through rough seas to arrive in Scotland on May 1, 1590.

The belief that Anne’s stormy voyage was caused by witchcraft, voiced by Danes, fascinated James. He began investigating witch hunts and attended the 1590-1592 North Berwick witch trials in eastern Scotland, and personally supervised the gruesome torturing of women accused of being witches. He later wrote Daemonologie in 1597, which provided background material for the Weird Sisters in Shakespeare’s Tragedy of Macbeth. Over time he became more skeptical, and warned his son about being wary of accusations.

Moving to London

James VI of Scotland became James I of England when he united the crowns in 1603. He reigned over 3 countries, including Ireland, for 22 years until his death. His chose England for his court, embracing theatre, art, material wealth and literary achievements during this late Renaissance period. Ignoring his promise to return to Scotland every 3 years, he only visited once.

Ten days after King James I took the English throne in 1603, he sponsored Shakespeare’s troupe, renamed them ‘The King’s Men’ and required them to perform regularly. Shakespeare wrote many plays tailored for James, including the Scottish play Macbeth, based on history.

James’s firm belief in the divine right of kings caused conflict with Parliament frequently. He was also criticized for his open physical affection with male favorites at court, and his practice of elevating them to high positions—such as promoting George Villiers to the Earl of Buckingham.

As a staunch Protestant, he agreed that the Bible be separated from the Catholic Bishop’s Bible. He authorized the English translation of the King James Version of the Bible, which 47 scholars collectively completed in 1611.

Suspicious Death

King James I died at age 58, in 1625. He became ill from a malarial fever but doctors believed he would fully recover. James’ favorite, George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, never left his side. As James became increasingly frail, rumors spread that George poisoned the king, as he had given him a cordial to drink without medical consent. His condition worsened and James died of a stroke and dysentary a couple weeks later, with both George and son Charles beside him.

Parliment accused George of poisoning James, potentially with Charles’ cooperation, and attempted to impeach the Duke of Buckingham. But Charles, now King, dissolved Parliment before they could act.

King James I and Queen Anne are buried in Westminister Abbey.

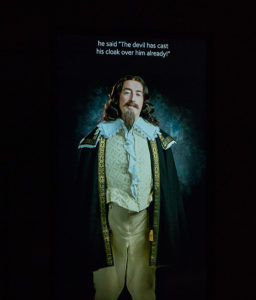

Queen Anne & King James VI

Queen Anne of Denmark

Anne was 14 years olf when she arrived in Scotland. She adored Dunfermline, especially her new Palace. Since monks no longer resided there, she extended her living space and spared no expense decorating a new stand alone dream mansion.

She was a fashionista who loved jewels and elegant parties, but also enjoyed hunting with her hounds at nearby Falkland Palace (which had been a favorite of her mother-in-law, Mary Queen of Scots).

Anne, who grew up Lutheran, began leaning toward Catholicism in the mid 1590’s, which caused much friction in Presbyterian Scotland. AND in her marriage.

When their firstborn, Henry, was born in 1594, James insisted that he be raised in Stirling Castle by the Earl of Mar. James wanted to protect Henry from being influenced by his mother’s religious views. Anne was furious about being separated from her son, and voiced her angry tongue in public. James ordered the Earl to keep Henry from Anne at all costs “even at my death,” which led to scenes of rage between the royal couple and caused their separation thereafter. Anne lived in her lavishly adorned Queen’s House in Dumferline Palace, and James lived in Edinburgh.

Despite their separation and intolerance of one another, they had six more children. Anne decorated a nursery for her 2nd baby, daughter Princess Elizabeth. But James took the baby away, again, this time to Linlithgow Palace. Only her younger sons, Robert and Charles were allowed to remain at Dunfermline with their mother. Robert died at 4 months, and is buried in Dunfermline Abbey. Son Charles, the last monarch born in Scotland, later succeeded his father as king.

Moving to England

When English ruler Queen Elizabeth I died in 1603, James VI of Scotland also became King James I of England. He immediately he left for London with the Earl of Mar. Seizing the opportunity to collect her 9 year old son, pregnant Anne traveled to Stirling with an entourage of supporters. But Henry’s caretakers refused, causing her such stress that she miscarried. When James ordered Anne to join him in London, she wrote a letter stating she would not join him unless she could bring her son. Months later, her demand was granted. Anne and prince Henry traveled in her silver coach, stopping at St. Giles church in Edinburgh enroute to Windsor Castle. Their journey drew an enormous crowd of onlookers along the way.

When King James I and Queen Anne were crowned at Windsor Palace, Anne embarrased him when she refused to take the Anglican communion. Her behavior raised suspicions from Anglican clergy, who watched her carefully. Years later when Sir Standen brought her a rosary from the Pope, James imprisoned him in the Tower of London for 10 months. Anne’s sons both married Catholic wives.

Queen Anne embraced London’s high society, and freely spent her dowry on entertainment, jewels and travel around England, especially Bath. (One weekend cost £30,000…in the 1600s!) She loved dancing and masques, which Protestants frowned upon. She employed females to perform in extravagent masques, and sometimes performed with them in shocking attire.

On November 6th, 1612, daughter Elizabeth was busy planning extravagant festivities (cost £50,000) for her upcoming Valentine’s Day wedding, when 18 year old son Henry suddenly died from typhoid. Anne was inconsolable. Essentially losing her two oldest children, she withdrew from cultural and political activities. She hosted her last masque in 1614, and dismissed her noble court.

Queen Anne developed gout and dropsy, which debilitated her for two years. Son Charles kept close to her side in Hampton Court Palace. But King James only visited Anne three times, and didn’t attend her funeral when she died, at the age of 44, in 1619.

Charles I

Charles was the last monarch born in Scotland. Queen Anne delivered him in Dunfermline Palace, and raised him there for 3 years until she moved to England to join King James. Young Charles, who had been frail since birth, was 4 before he could walk ‘down the hall without a stick.’ His caretakers continued to work with him in Dunfermline for a year before they moved in with his mother in London.

Bay window in Royal Nursery upstairs

Charles became king of three kingdoms at age 19. Parliment members strongly opposed his proposed marriage to Princess Henrietta of France who was a Roman Catholic, but he married her anyway. He went against Parliment again when he used funds to aid France against Spain in the 30 Years War. When Parliament limited funds, he dissolved them and raised taxes instead.

Parliment distrusted Charles, as they suspected he may have played a role in his father’s death, and were afraid of his attempts to remove Reformation practices and revert to Catholicism.. King Charles refused to call Parliment to session for 11 years, believing like his father, in the king’s divine right to rule.

Charles reintroduced Bishops to govern the church, and appeared to oppose Presbyterian views. When the Church of Scotland abolished Bishop rule in 1638, and produced the National Covenant, King Charles interpreted their actions as an open rebellion of his authority. Conflicts between the king and Parliament, namely religious differences, led to the English Civil War.

English Civil War

When the English Parliment reached out to Scotland for support against Charles, the Scots promised military aid in exchange for religious demands. England agreed to extend Presbyterian beliefs across Great Britain according to the Covenant of 1643. But 5 years later, the English had enough armed forces led by Oliver Cromwell, and no longer needed Scottish support. Charles surrendered to Scottish forces at Newark. Turned over to the English Parliament, he was imprisoned in 1647 while a 2nd Civil War ensued. Armies led by Oliver Cromwell crushed Wales and Scotland.

King Charles was tried for high treason in 1649. Parliment severed ties with Scotland, and was a declared a Republic. They passed a law prohibiting Scotland to name a successor on the very day that King Charles was executed. (In defiance, Scotland immediately named Charles II as King of Great Britain, France and Ireland.)

King Charles was beheaded on Feb 5, 1649. Ironically, he is buried in the same vault as King Henry VIII who created the Protestant Church of England when he broke from the Roman Catholic church. Wonder if their souls collide?

King Charles of Scotland

Charles II

He was the last monarch to live (briefly) in Dunfermline Palace in 1650.

Age 18 when his father was executed, Charles II was living in France with his mother. The Scottish Parliament named him as their new king the same day his father was killed. Inviting him back to Scotland, they pressured him to sign a declaration at Dunfermline Palace on Aug 16, 1650. Although he secretly opposed, he agreed to obey the religious Covenants and promote Presbyterian beliefs in surrounding countries, among others requirement to become the Scottish king. Cromwell defeated Charles II in battle inn 1651, and took authority of the 3 countries. Charles fled in exile.

Political unrest following Cromwell’s death led to the restoration of monarchy in England in 1660. As a result, Charles was invited to return, and was crowned King of Scotland, England and Ireland on his 30th birthday. He ruled for 25 years. The ‘Merry Monarch’ had 12 children with numerous mistresses but no legitimate heirs. Charles II believed in religious freedom, and attempted to provide personal choice. But the English Parliament forebade this. Nine years later, the king dissolved the Parliament and quietly converted to Catholicism before his death.

Charles II died of a sudden stroke in 1685. Suspicions arose of being poisoned. But doctors later ruled the likelihood of kidney failure from mercury exposure during his ‘experimental interests.’

Visit Dumfermline Abbey Church

After the Reformation, in 1570, the Catholic church (founded by St. Margaret in 1090) became Presbyterian.

The church building was in a sorry state, having gone through a Protestant ‘cleansing’ in 1559 and 1560. Three years later, roofless, it fell to ruin. By 1672, the choir area had collapsed, and worship services were moved to the Nave.

In 1818, architect Mr. William Burns was hired to rebuild the church. The renovated Abbey Church reopened in 1821 and is still holding services 200 years later.

Bruce’s Lost Tomb

During the renovation in 1818, workers found a hidden vault. Inside was a 5 ft 11 inch skeleton that had a cut through his sternum. Gold embroidered linen was laid over the lead covering. Historians examined the details carefully, such as the handmade nails, markings from the stone masons, and gold coins. They made a cast of his head and determined it was in fact the remains of Robert the Bruce whose tomb had been lost within the Abbey since his burial in 1329.

In 1889, with great pomp and glory, the hero was laid to rest under the High Alter. The memorial plaque is a golden brass engraving of the life-sized king set in red marble. Hearts depicted in the corners of the plaque remind the visitor that his heart remains in Melrose Abbey.

A bronze cast of Bruce’s head sits in a glass case. New since our visit is a long overdue permanent exhibit. Museum quality plaques display detailed written information about his life, accomplishments, and his lost tomb. (Exhibit pics on their website are impressive!)

The Abbey Church was redecorated again in the mid 1980’s. Sunday services led by Reverand MaryAnn Rennie are currently being live streamed on Youtube, due to Covid restrictions. Tourists can visit in person except Sunday and Monday but must reserve a spot online on the Abbey Church website.

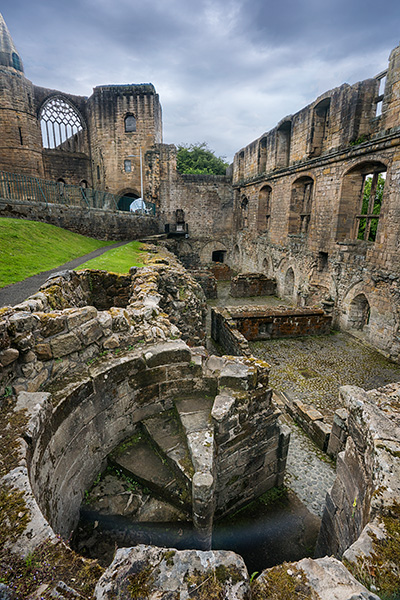

Visit Dumfermline Palace & Monastery

*Normally open April to September, it’s currently closed due to Covid. Check website for updated info. But even without tickets you can see the ruins from a distance. Location: south side of the Abbey.

The tourist entrance is opposite the door to the Abbey Nave. Follow the wooden walkway overlooking the ruins. Enter the little shop to buy tickets, and look at the recovered stone carvings in the museum room before descending a narrow spiral staircase to reach ground level.

To visit the Palace, follow the path that parallels the long stone wall and the Abbey beyond it. To visit the Monastery, head the opposite way. Walk under the arched opening of the Gatehouse to access the inner courtyard to visit the ruins of the Refectory.

You might recognize the locale from the movie set of the Outlaw King about Robert the Bruce.

Monastery

Queen Margaret founded the massive Benedictine Monastery in the 1072 near a wooded Glen. A grand building of three levels, it once connected to the Abbey.

The Refectory is where Benedictine monks ate their communal meals.

Food was stored in the basement cellars. There was an ample supply of venison, game birds, fish, honey (monks kept bees), wine and ale (water could carry disease), vegetables, fruit, meat, and flour.

Life for the Benedictine Monks who lived here was very strict. They followed the rules that St. Benedict wrote 1500 years prior in Italy. Every hour was accounted for. They wore long black robes with hoods and spent the day performing manual labor, praying, studying, bathing or worshiping. Sleep was limited to 3 hours slots as they were expected to go to the monk’s choir of the Abbey through the night.

where the monks slept

Monks weren’t the only ones who lived in the Monastery.

In the 1200’s, it was traditional for Abbeys to provide housing for pilgrims who traveled there, whether rich or poor. People of lower social class would sleep in nearby hostels but upper class would stay within the walls of the Monastery guesthouse. According to Benedict practices, the Abbot would dine with the travelers, considered his guests. And there were many guests…people flocked to St. Margaret’s shrine praying for blessings and miracles.

Pilgrims weren’t the only guests. Monarchs and nobles stayed overnight to visit the royal couple or simply stay as a matter of convenience enroute to their other castles. Mary Queen of Scots stayed overnight here many times between 1562-65 traveling between St. Andrews and Stirling, Perth or Falkland. And had she not been imprisoned, would’ve certainly visited her son and grandson who later lived at the Palace.

The guesthouse began as a simple wooden structure, but transitioned into a stone Palace during David’s reign.

Beginning with the reign of King David, monarchs ruling from Dunfermline also lived in the guesthouse of the Monastery, later known as the Palace. Kings and Queens changed and remodeled their living space according to their individual preferences.

English troops and later religious zealots burned and attacked the monastery and palace buildings during the uprisings in 1330 and 1560.

Palace

When King James VI gave the renovated Palace to Queen Anne as a wedding present, the Reformation had ended and monks were no longer living here. Anne turned the Palace into a showpiece. She added a 3rd floor with many windows.

The ground floor had separate guestrooms, plus a magnificent banquet room. Tapestries hung on the walls of the 90-foot Great Hall, which had elaborate windows overlooking the Glen. A spiral staircase in the center of the Palace led to the Royal Apartments.

Prince Henry and Princess Elizabeth were born in the royal nursery, a room with a commanding view overlooking the countryside. It must’ve been a special place for the Queen to bond with her babies before they were taken away at 6 months of age to be raised by separate families in Stirling and Linlithgow Castles. The King allowed only their 2 youngest sons to stay in Dunfermline with their mother.

Royal staff lived and worked in the basement. Vaulted chambers below ground included a storeroom and a mysterious subterranean passage of 200 ft, its purpose unknown.

In 1708, one of the worst snow storms hit Dunfermline. Snow fell for 8 straight days, covering streets up to 20 feet deep. The snow, and heavy frost that lasted 3 months, contributed to the demise of the Palace. By spring the north gable and roof had collapsed, leading to irreparable ruin.

This Annunciation Stone once decorated the interior of a Palace window

Queen’s House

Anne built a stand alone mansion called the Queen’s House as her private residence after her children were taken away. She wanted to live apart from the King! So she hired William Schaw, the King’s master stone mason, to build her mansion just outside of the Abbey’s main entrance. From her 3rd story window, she could see Queensferry and the Firth of Forth.

Nothing remains of her mansion today. In fact, the city demolished it in 1797 after locals used the largest room for cockfighting– the ‘worst vandalism to hit dunfermline.’

Visit Dumfermline Carnegie Library & Galleries

Right across the garden from the Abbey Church is a modern green-glass cornered building that hosts a Carnegie Library, Gallery, and Museum. All free. Plus a delightful cafe upstairs that serves hot scones, homemade soup and tea.

Right across the garden from the Abbey Church is a modern green-glass cornered building that hosts a Carnegie Library, Gallery, and Museum. All free. Plus a delightful cafe upstairs that serves hot scones, homemade soup and tea.

Peek inside Andrew Carnegie’s first library. Opened in 1883, this library was the first of 2,509 libraries the generous Scottish American philanthropist would fund across the world. When it opened, Carnegie Library had a flat for the librarian (highly coveted position), a smoking room, recreation room, separate ladies’ and gentlemen’s reading room and music room.

Wander next door to the Gallery to see rotating exhibits. Then go upstairs to visit the Museum, new in 2017.

The Museum has 6 themes: Industry, Leisure & Recreation, Transport, Conflict, Homes and Royal Dunfermline. My favorite part of the Museum was watching the short film about the Royals–don’t miss it! Fascinating to hear the stories as costumed actors embody different royals– Queen Margaret of Scotland, King David the First, Queen Anne of Denmark, King Charles I and King Robert the Bruce. (film photo above of Queen Anne & King James)

And don’t forget to pop in to the cafe… enjoy a fresh scone with a view!

Visit Dumfermline Pittencrief Park

Pittencrieff Park is a serene public park steps away from Nave of Dunfermline Abbey. Called the Glen, this 76 acre park has a rocky ravine that runs through the middle of the park. This is where the originator of this ancient royal city, King Malcolm III, lived in a stone tower with his saintly Queen. Located high on Tower Hill, the fragmented ruins of the tower exists still today. If you know where to look…

All 8 of King Malcolm & Queen Margaret’s children were born in the tower: (And all buried in Dunfermline Abbey except 2 daughters.)

Edward – died in battle with his father in 1093

Edmund – died a Monk

Ethelred – died an Abbot

Edgar – `The Peaceable’ died 1107

Alexander – `The Fierce` died 1124

David – `The Sair Sanct` died 1153

Mary – of Boulogne died 1116

Matilda – married Henry I of England died 1118

When my daughter and I came to visit Dunfermline, we had no idea about the historical significance of the park. And apparently missed the nearby sign (on a walkway near the Abbey entrance) pointing to Malcolm’s Tower.

When my daughter and I came to visit Dunfermline, we had no idea about the historical significance of the park. And apparently missed the nearby sign (on a walkway near the Abbey entrance) pointing to Malcolm’s Tower.

We walked across stone steps in the forested paths in the ravine (where the Tower once stood) and over old stone bridges crossing a stream. We didn’t realize, then, that it was the birthplace of so many little princes and princesses who once romped through this very park.

Or that Queen Margaret’s cave was a short walk away in the Glen, somewhere northeast of the former Tower.

One story goes that King Malcolm followed her one day, suspicious of her frequent disappearances. Fearing the worst, he hid from her view. When he observed her entering a 6×12 foot cave, and simply praying, he was so overjoyed, that he hired stone masons to carve out niches for statues and candles.

Neither did we know that Sir William Wallace hid in Pittencrief Park– frequently– to escape his enemies. He lived in both a 4-ft cave and at times in St. Margaret’s stone cave well. The Glen by that time was an impenetrable forest, perfect as the hiding place for Scotland’s exiled hero.

Had we seen a tourist pamphlet or map identifying these landmarks we surely would’ve looked for them…

After the death of Malcolm and Margaret, when the Tower was no longer inhabited by a king, the surrounding lands of Pittencrieff were given to Obervilles, a noble Norman family. But during the Wars of Independence, Robert the Bruce kicked the Obervilles out for being English, and gave the lands to the Wemyss family in Fife for their generous aid and support.

On its own, it’s a pleasant place to stroll. The pretty park has flower beds, a glass greenhouse, arched walkways and even peacocks. There’s even a historic double arched bridge, 20 ft above the other, somewhere around Malcolm’s old Tower.

And who knows how old this arched passageway is?

Pittencrief Park was purchased in 1902 by Andrew Carnegie, who donated the park to the city. He grew up a few blocks away. His birthplace cottage is an excellent museum to learn about his life, journey to America, fortune in steel and generosity giving away most of his wealth.

Since being home, I’ve learned that there IS a musuem about the history of Dunfermline inside the park—the yellow Pittencrief House. There’s also a cafe and playgrounds. The city sponsors many festivals in the park, from music concerts and food festivals to the Robert the Bruce festival in summer months.

The day we visited the park (mid-June) was very quiet. We only spotted one couple, a mother pushing a stroller and a jogger that afternoon. Even the peacocks were hiding.

Logistics to Visit Dunfermline

Located 13 miles north of Edinburgh’s international airport, Dunfermline highlights can be seen on a day trip if limited on time. Buses and trains travel here regularly from Edinburgh and Glasgow. But why rush?

Visit Dunfermline slowly, and it will reveal itself in layers—especially now that you understand who lived here and their history.

And know where to look!

Jenise - Fantastic to have all this history in one place. Thank you!I’ll be there next year!

Kim Walker - You’re welcome…enjoy Scotland!